Nostalgia is a funny thing. I’ve experienced it in memories of childhood, of our early marriage, of good friends, but I never expected to find it when thinking back to our daughter’s earliest surgeries, moments filled with shock and apprehension. Yet this week that’s what happened.

On Friday, Gabriella had an appointment with the ophthalmologist. She sees him only every couple of years, which is a good sign. It was to be a late morning visit, and Lisa reminded me that his office is often crowded, the waits long.

This would be the first time I had accompanied them to his office in twenty years. On the roster of medical specialists our daughter has seen over time, he has long been routine.

It wasn’t always that way. We discovered a milky blurring when she was six months old and learned soon after that she had cataracts. She was already seeing an ophthalmologist for strabismus, and he performed four separate surgeries for this new problem, two each to remove the cataracts and to implant intraocular lenses, plus a fifth to correct the crossing of her eyes.

The two excisions were her first two operations, her first exposure to anesthesia, our first exposure to the surgical waiting room. By the time he had inserted the second artificial lens, however, our daughter’s medical situation had grown more severe. Our frustrations over getting her to accept glasses or contact lenses paled alongside the need to break several bones to correct her clubfoot. Or multiple surgeries to remove a tumor affixed to her skull.

All of this is two decades in the past, but it still casts a long shadow over our lives. And yet I looked forward to this doctor’s appointment.

In the late morning, we got Gabriella ready and into our adapted minivan. The office is half an hour away, and we arrived fifteen minutes early. As I had before, I appreciated that he was the rare pediatric specialist who continued to see our daughter after she turned twenty-one.

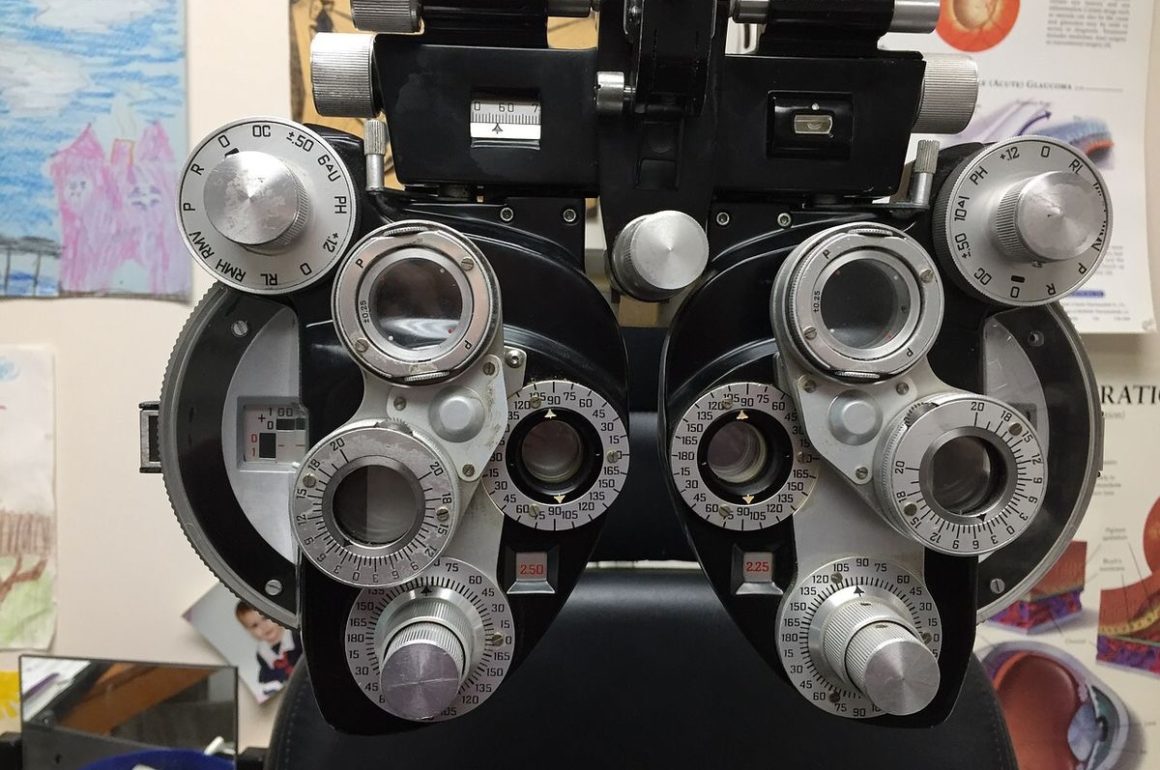

Soon they called her name. A medical assistant led us into an outsized examining room. More than the handicap parking space at the end of the long row of exterior doors, more than the waiting-room with the bead-maze toys, this spot brought back memories. All around were pieces of equipment I recognized, even if I had never learned the names of any. And my déjà vu increased when her doctor came in.

Life with Gabriella has introduced us to the best and the worst of the medical profession. We had a geneticist with a miserable bedside manner. One surgeon couldn’t be bothered to let us know that the malignant frozen section was wrong, that our child didn’t have cancer. But there have been many more amazing physicians, neurologists and orthopedists and neurosurgeons, and this man, Dr. Engel, Gabriella’s only ophthalmologist over all that time.

We looked at each other with big smiles, we shook hands, we exchanged pleasantries. Two decades had grayed his temples and left a few lines on his face, but those kind eyes brought that spark of nostalgia. The eyes of an eye-doctor, they had reassured us and buoyed us and comforted us in those first unstable days.

Back then, his practice was small. When we met, he extended his hand and said, “Call me Mark.” Of all of her doctors, he was the one that felt like a colleague. A friend even.

He examined her on Friday with the same gentleness and easy command I remembered. Unlike the visual exams I’ve experienced, there was no eye chart with rows of shrinking letters, no refraction test with the fancy device with all those rotating and clicking lenses. He assessed her vision using measurements of the eyes, he puffed air to evaluate the risk of glaucoma, and then he dilated her pupils and we sat back in the waiting room before returning for him to examine the backs of her eyes. He also checked the intraocular lenses, which have held up well since she was three.

Then it was time to say farewell until her next appointment in two or three years. We shook hands again and headed out, and I felt a warmth I’ve rarely known in medical offices.

Nostalgia comes in the most unexpected places.