Today is Super Bowl Sunday, with a lot of focus on winning. We live in a culture that values winning, in some ways to too high a degree. It makes me wonder, what is winning in a family like ours?

Since childhood, I’ve been a fan of the New England Patriots (my apologies to all those Patriots-haters out there) even though I lived in New Jersey. As an eight-year-old, I chose my football team with a logic not unlike amateurs at the racetrack betting based on liking the horse’s name: I liked their helmets. For my first 30 years following the Pats, I endured disappointment and embarrassment, but over the past sixteen seasons we’ve enjoyed a lifetime’s worth of winning.

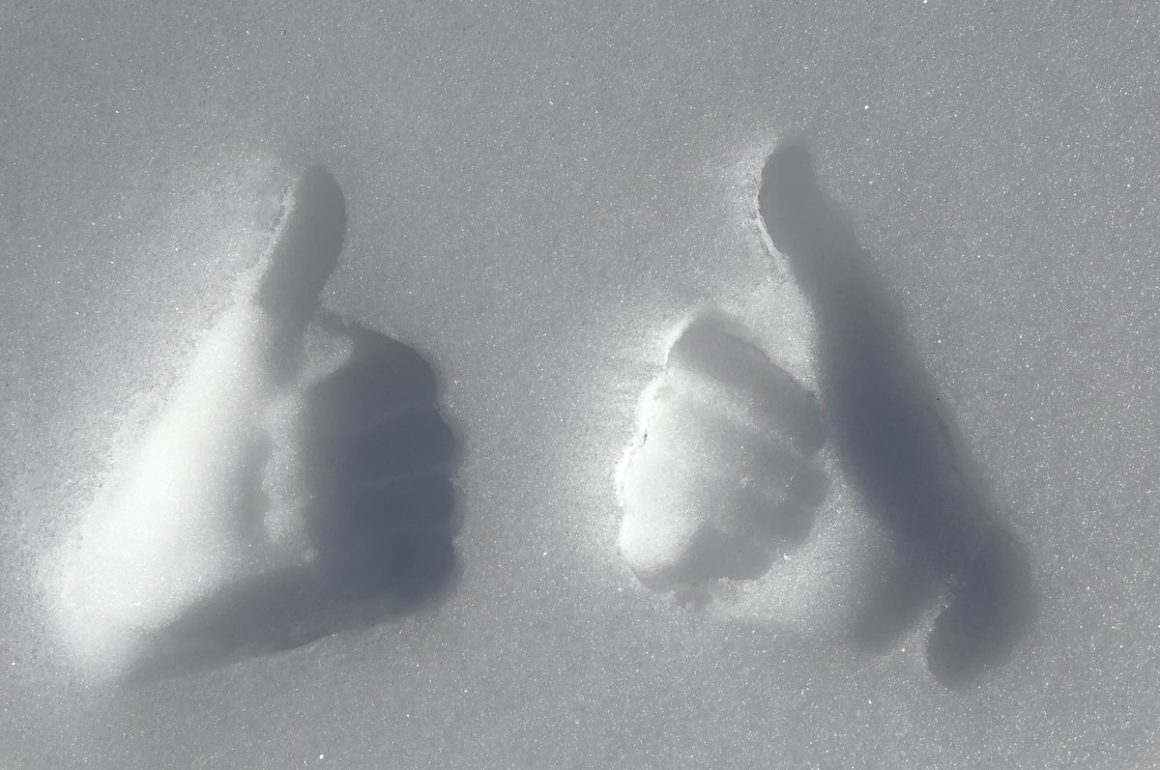

I’ll never forget the first one, in early February 2002. Gabriella was seven years old, and she sat in an adapted stroller. We used to put her to bed by eight o’clock, although even then she took hours to drop off. But the Super Bowl started around 6:30, so I had her sitting beside me as I watched. Every so often, we’d sing along to Rock’n Roll Part 2. When we reached the Hey! parts, I’d lift her arms and she would giggle, bringing me a joy as vivid in my memory as the game-winning final drive.

In sports, as in much of life, winning is cut-and-dried. Growing up, we all gain experience with winning and losing. As children, we contest races and board games, and as we grow older we compete in sporting events and for scholarships, and then in adulthood we seek to win the hand of the person we love or success in our chosen careers. Lisa and I have tasted such victories in our lives, and we’ve seen Alexander begin to enjoy his own triumphs.

Winning is different for Gabriella.

We knew from early on that she would never win in the traditional sense. Cognitive delays meant she would not capture any academic prizes, nor would she be mainstreamed into the public school system. Her low muscle tone made athletics impossible, even in the Special Olympics. I mourned the loss of opportunity, the isolation from such hallmarks of American life. It was only later that I realized that isolation was more ours than hers.

The wisdom of the passing years taught me that Gabriella was winning in other ways. Her perseverance helped her survive dehydration and surgeries, and multiple bouts with pneumonia and debilitating seizures. She succeeds at things that might seem insignificant to us, like reaching out to secure a nearby toy. Often she wins our attention when she decides we have ignored her for too long. And she wins the heart of everyone she meets, with her smiles and clicks.

My perspective has changed over two decades, in ways I could never have imagined. Small victories came in nights of uninterrupted sleep, in seasons without illness, in years with no hospitalizations. There were bigger triumphs to relish, like getting our school district to agree to allow Gabriella to attend Lakeview, or convincing her health insurance provider to continue her nursing.

But most of all, I’ve come to appreciate what really matters, simplicity and peace, friendship and love. Lisa feels the same way, as do our family and close friends. So while I’ll spend this evening rooting for the Patriots, whatever happens on the football field, we’ve already won.